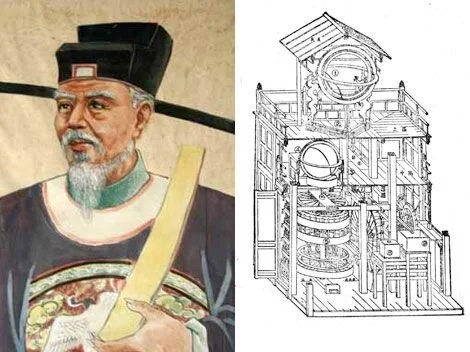

Su Sung was a diplomatic envoy to the Sung dynasty, that ruled China during one of the most important cultural periods from (960-1279 AD).

In 1077, Su Sung was sent by the Sung emperor to wish a ‘Happy Birthday’ to the ruler of the Khitan people further north.

This ruler’s birthday fell on a winter solstice that year, so when Sung arrived, he was shocked to find he was a day early. Su Sung knew not to expose his emperor’s horological inferiority, so he convinced the hosts to entertain one day early. Nonetheless, this mix-up showed that the ‘barbarians’ to the north actually had more accurate timing tools than the Sung dynasty!

When Su Sung returned home, the emperor asked Su whether the ‘barbarian’ calendar or the Chinese calendar was correct. Su told the truth and upon finding out the barbarians were more accurate, the Chinese emperor fined and punished all of the officials related to the Astronomical Bureau.

Su Sung then received the Emperor’s direct orders, instructing him to create an astronomical clock that was more utilitarian and more beautiful than any other clock to exist!

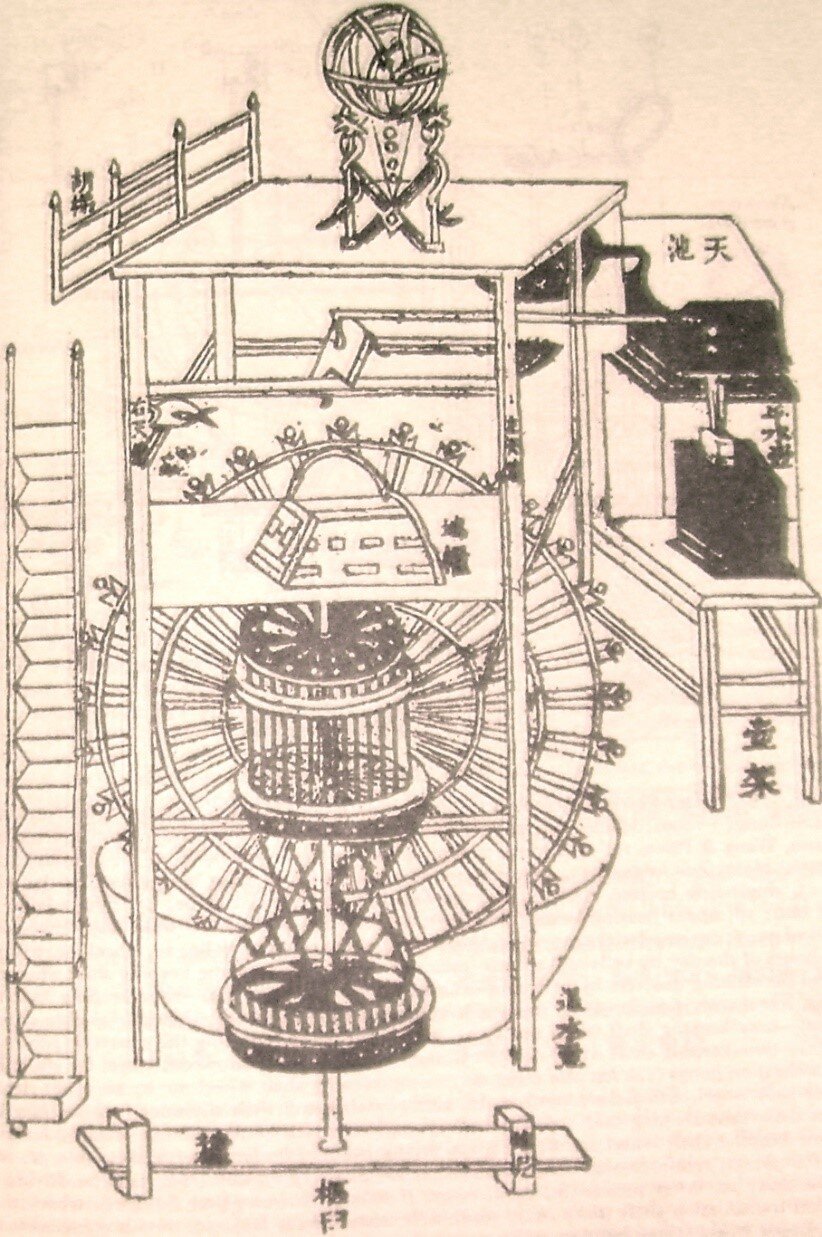

Su Sung got to work. His mission: “a new design for a mechanized armillary sphere and celestial globe.” He created a thirty-foot-high astronomical clock that spanned a total of five stories.

Su Sung’s clock tower / Credit: Line 17QQ

On the top platform there was a massive bronze, power-driven armillary sphere. Within this armillary sphere lay a celestial globe. Inside the main tower, that was three stories tall, was a huge water clock. This was powered by water flowing on the ground level and filling/draining sections of water on the rotating wheel.

The outside of the structure featured mannequins that carried bells and gongs that would sound at desired times (the quarter hour being one example). These mannequins also marched as the clock operated giving the viewers a show at various points throughout the day. All the mannequins’ movements were controlled by the clock’s machinery.

The main element of this water clock? The escapement. Su Sung had created a brilliant water escapement.

Su Sung’s drawings of the mechanical components of the water clock. / Credit: International Symposium of History of Machines

Playing off the fluid properties of water, Su created the ‘Staccato motion’ required for a mechanical timepiece with his water escapement. This is just as the Europeans did by playing with the elastic properties of metal in the ‘Verge escapement’. Su’s water clock was very similar to the mechanical clock developed by the Europeans hundreds of years later.

By 1090, this clock was finished. It was ready to entertain, clock the planets and the stars, and to keep track of the time.

The astronomical clock ran from 1090-1126, until it was stolen by invading Tatars. However, the Tatars were not able to comprehend the complex clock working again once it was deposited in its new location - Peking. This marked the end of Chinese high horology for the time being. Even worse, before the Tatars stole Su Sung’s masterpiece, Taostic reformers came into power. Taostic reformers were not fond of ‘fancy’ timekeeping and did little to continue horological development.

Unfortunately, Su Sung’s book that he wrote on the design and operation of this clock was lost to the West until the 17th century. By then, the mechanical clock was much more technologically advanced, and the Europeans effectively put their ‘stamp’ in the horological history books with the advent of the weight driven mechanical clock in 1283.

Now this isn’t to say that Su Sung was the very first person to create the mechanical clock. It is documented that there was another Chinese mathematician and astronomer named “I-Hsing” who created the first mechanical clock at some point in his life between 681 and 727 AD. More Chinese horological development lost to history.

It is remarkable just how advanced Chinese horology was back then. Upon its completion in 1090, Su Sung’s water clock would have been the most cutting-edge horological device on the planet. To put things in perspective, The Catholic Church didn’t have their first weight driven mechanical clock until 1283, Christiaan Huygens’s didn’t patent the pendulum clock until 1657, and Su Sung’s clock was only decommissioned in 1126. Imagine how much farther horology may have come had the Sung Dynasty and its successors continued to emphasize horology? It’s quite something.

In a book called “The Genius of China – 3000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention”, the introduction titled ‘The West’s Debt to China’ explains that one of the greatest untold secrets in history is the effect that China has had on many of the modern-day inventions Westerner’s still use today. And Su Sung’s clock is just one of the many contributions from Chinese civilization over the millennia. This also recalls China’s increasingly central role in the world of watchmaking today, and as such, their modern contributions to horology.

Su Sung (1020-1101) / Credit: History.Cultural-China

By: Eric Mulder

Read more:

"Su-sung." Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery/Encyclopedia.com, April 15th 2021, https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/su-sung.

“Song Dynasty - Chinese History.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Song-dynasty.

Boorstin, Daniel Joseph. The Discoverers: A History of Man's Search to Know His World and Himself. Phoenix, 2001.

Lienhard, John H. “No. 120: Su-Sung’s Clock.” University of Houston, https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi120.htm.

Max. “Mechanical Clocks.” Vendian, http://www.vendian.org/guests/invent/max2.htm.

Andrewes, William J. H. “A Chronicle of Timekeeping.” Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-chronicle-of-timekeeping-2006-02/.

“I-Hsing.” Oxford Reference, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095957300.

“Huygens, Christiaan.” Encyclopedia of Math, https://encyclopediaofmath.org/wiki/Huygens,_Christiaan.

Temple, Robert. The Genius of China. 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. Chinese Science, vol. 10, International Society of East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine, December 1991.